Imitation Gem

Emerald and Ruby

BnF Ms Fr 640 p100v RECONSTRUCTION OF IMITATION GEMSTONES

2015.10.16

making and knowing lab, chandler hall9:05am

Emerald Trial 1:

1.5+ hrs spent as a group deciphering problems in the manuscript and its translation. These mostly revolved around understanding a "dram" and "un gros (de sel)". Re: dram, we were not sure if this was meant to equal 3.54g or 1.77g as per Avoirdupois system. We settled on 3.54g after consulting other sources, namely Middle French dictionaries.

8 drams made 1 oz = 8 drams = 28, 34 grams - Cotgrave:https://books.google.com/books?id=ISi4M196tl4C&pg=PT221&lpg=PT221&dq=cotgrave+dram&source=bl&ots=AEqZMFf_sx&sig=FJjgDLl1ELXqeY7yYmAueloCd2I&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CDYQ6AEwBGoVChMItej73prHyAIVBqkeCh3cBwOj#v=onepage&q=cotgrave%20dram&f=false

Next was the issue of "un gros de sel" written in a marginal note, and how exactly to translate "un gros de". A pinch? A piece? Coarse salt? "Gros sel" appears multiple times in the manuscript but "gros de sel" does not.

We decided on 3 trials with varying additions of alkali salt [this was ultimately not realized]

- 1:3:1 (quartz powder:red lead:alkali salt)

- 1:3:1/2

- 1:3:2

10:45am

preparing to begin

We are using:

3.5g Kremer 58620 Quartz Powder (in tub, not coarse one in plastic bag)

10.6g Kremer xxxxx Red Lead (in tub, wrapped in plastic)

3.5g Kremer xxxxx Potash (potassium carbonate, in tub)

BEWARE: red lead is incompatible with aluminium, it can form an explosive compound.A reminder to always look (and re-look) at safety data sheets!SET UP in FUMEHOOD:To prepare for the process of mixing, I first thoroughly wiped down the entire surface/ground of the fume hood with wet paper towels, then wiped it down again with a dry paper towel. We then spread out newspapers across the entire surface, several layers thick (as many sheets as could comfortably slide under the vertical poles at the rear of the fume hood--approx. 2-3 sheets). Next we spread out damp paper towels, particularly in areas where there would be lead. A glass plate was set on top off the wet paper towels and then topped with a wet paper towel to prevent the copper sheet on top of it from sliding around. All the ingredients were placed on the left side of the fume hood interior--in their plastic tubs. Two stainless steel "scoopers" and one plastic spoon (for red lead), the scale with a beaker on top of it (set to weigh in grams).Trial #1I measured out 1 dram (3.5g) of the quartz powder into the beaker. I replaced the lid onto the tub of quartz powder and placed the scoop I had used next to it to make sure I only used it with that one substance. I transferred the powder onto the copper sheet by gently pouring it out--tipping the beaker with its lip touching the sheet and slowly raising the bottom of the beaker up, gently tapping the back to get all of the powder out. I consolidated the powder using two small palette knives. I reached for the muller and placed it on top of the powder to begin grinding and was surprised at how much seemed to blow away because of the way I placed the muller down. I did not force it or move too quickly, but I needed to be even more gentle--the powder is extremely fine. I reconsolidated what had blown away, pulling it forward with the palette knife, and very gently set the muller down on top of it a second time. I did not see any of the powder fly away this time.Grinding was quite challenging to start--I was worried about the powder blowing away and also aware of how much powder was on such a small copper sheet. I would have felt more comfortable if we had had a larger copper sheet, but given the small size of it, it seemed like a lot of the powder could easily be pushed off the sheet and end up on a wet paper towel. I grinded with a lot of force, beginning in a small area and making a 'figure eight' shape as recommended by Marjolijn. Within a few minutes--maybe 2--the process was much easier. It is hard to say whether I simply became familiar with the material I was working with, with the movements, or if it was getting easier because it was being ground down. There was definitely a sound to the grinding, but to hear the sound it required a lot of pausing to reconsolidate the powder and begin grinding a different portion of the amount on the sheet. within 5 minutes, I noticed a color change in the powder; it had gone on the sheet and looked quite white, but as I would scrape bits of it back together with the palette knife, I noticed very clear distinctions between a white powder and a light gray powder. The more I ground, the more the powder turned gray. We also remarked on how much of the color of the copper sheet had changed. While grinding, we were simultaneously polishing the copper, making it seem like the powder must have been absorbing tiny bits of the copper which, we had suspected, would assist in turning the finished "gemstone" green. Marjolijn also suggested that it might be turning gray due to residual oil still on the muller. It would be good to make sure the muller is as clean, oil-free, and dry as possible.

We (Jenny, Marjolijn and I) took turns grinding the powder to get a feel for it. We felt it had been thoroughly ground when all of the powder had turned dark gray--I had taken my watch off but would estimate 10 minutes. Then, before incorporating the red lead, we followed safety instructions to prepare for working with it. Dust masks, goggles, and double layers of gloves, tapped around the wrists (this was not done so properly to start but I was retaped by Pamela shortly after). The safety person who was present asked if we could begin with a smaller dose of lead than was called for, as an addtional safety precaution because he said there might be some kind of reaction. We agreed to start with one dram (instead of three) to see if anything would happen. I lowered the fume hood slightly for extra precaution and opened the jar of red lead. With the plastic spoon, I began putting the red lead into the beaker. I was immediately struck by how much heavier the lead was than the quartz powder. I did not feel this in my hand because the spoon only had a small amount...but the scale was showing an increasing weight so much more quickly than it was with the quartz. There was a drastic difference in the weight of the two. 1 dram (3.5g ) was measured out. I closed the lid of the red lead jar and placed the spoon next to it. I gently put the red lead onto the quartz powder and combined the two with two palette knives. I began grinding it. It was very difficult to grind. It was hard for the muller to even move--it felt so sticky or gummy. I mentioned this to Pamela who was standing next to me and she said that the author of the manuscript uses words like fatty or greasy to describe lead. It not only looked like the color of cheetos cheese powder, but it felt like how I'd imagine grinding that would be...it's a powder but it's greasy and sticky. When you get the powder on your hands you can't really rub it off. It spreads like grease. So "grinding" this mixture didn't feel like grinding. There was little sound of grinding as compared to the quartz powder. But we continued. marjolijn and I were the only ones properly dressed/protected to do it, so we took a few turns and then she handed it off to me as she wanted to take photos. This continued and got slightly easier as time went by. I kept grinding and noticed a difference in color--the brightness of the red lead had gotten duller, grayer, as well. The grinding lasted approx 10 minutes.

When it was time to add the potash there was some discussion about whether it was necessary or not to grind it. Pamela and Marjolijn suggested that it wasn't really necessary. The manuscript says to add the alkali salt to a bronze cauldron and then grind. It seems that those with more experience in science or in glassmaking felt it didn't really matter whether it was ground or not. Pamela asked me what I wanted to do and I said I'd like to grind it...or at least crush the potash as they were in little balls. I definitely trusted that they knew what they were talking about (that it's not really necessary to grind) but I thought, since it says to do so in the manuscript, I might as well try to stay as close to it as possible.

I measured out 1 dram of potassium carbonate into the beaker, closed the jar and put its scooper next to it. I swirled the beaker around only briefly, maybe one or two swirls, and it was amazing how it began to turn orange. I had noticed a very tiny amount of red lead left inside the beaker from when I had measured it out (another sign of how "sticky" it is). These few little swishes of the potash seemed to scrub the red lead residue off very well AND take on the color...and from such a miniscule amount of lead. I poured the potash out onto the lead/quartz mixture in 2 doses because there were a lot of these litle balls and I didn't want them to roll off the copper sheet. I simply pressed the muller down on top of each bundle of potash balls and pressed down firmly, just moving my wrist in different directions to break the balls thoroughly under the base of the muller. There was quite a sound--little pops, explosions. It reminded me of both the sound and the sensation of eating pop rocks. Tiny little bursts, quite pleasurable to feel these things crackling under the muller. Once they were popped, I very lightly ground them in with the quartz/lead mixture. I probably would have done this slightly longer than I did but, as others had said it really wasn't necessary to grind the potash, I figured it was equally not so important to get the particles all well blended together.

I consolidated all of the powder/mixture with palette knives. Marjolijn handed me a winder palette knife thing with a rounded tip (sort of like a small spatula) and I used this to transfer the mixture into the crucible. All of the mixture easily fit into the crucible.

It's bright orange. We transferred the mixed powder into a crucible. Then clean up began in order to clear the fume hood for heating up the crucible.

all of the materials that had not had contact with the lead were removed--the jars of quartz powder and potash, their scoopers, etc. Marjolijn and I were the only ones in the protective gear to work with the lead so we worked on cleaning all of this under the fume hood. Everything that had been in contact with lead was cleaned with linseed oil. We cleaned the muller as you would an oil paint brush--she gave me paper towels with little puddles of oil, and I rubbed all over the muller's flat part as well as the body of it in oil. I then rubbed the flat portion on clean paper towels until there was absolutely no red lead smearing across the towel. We thoroughly cleaned the palette knives, etc in a similar way, and these were then washed with soap and water. We gently collected all of the newspapers and wet paper towels that were under the fume hood. It was amazing to see just how far some of the red lead had spread. Its color is so striking, it's quite easy to see small particles against newspaper print. We had to slowly bundle everything up, making efforts to do so carefully so that particles would not drift off the newspaper and onto the surface of the fume hood. When all was properly removed from the fume hood, we removed our gloves and put them in the hazardous waste container, then thoroughly washed our hands, wrists, and upper arms.

Joel then began setting up for the 2nd part of the experiment: heating the crucible.

He used a self-built furnace and I need to talk to him about exactly how he set it up.

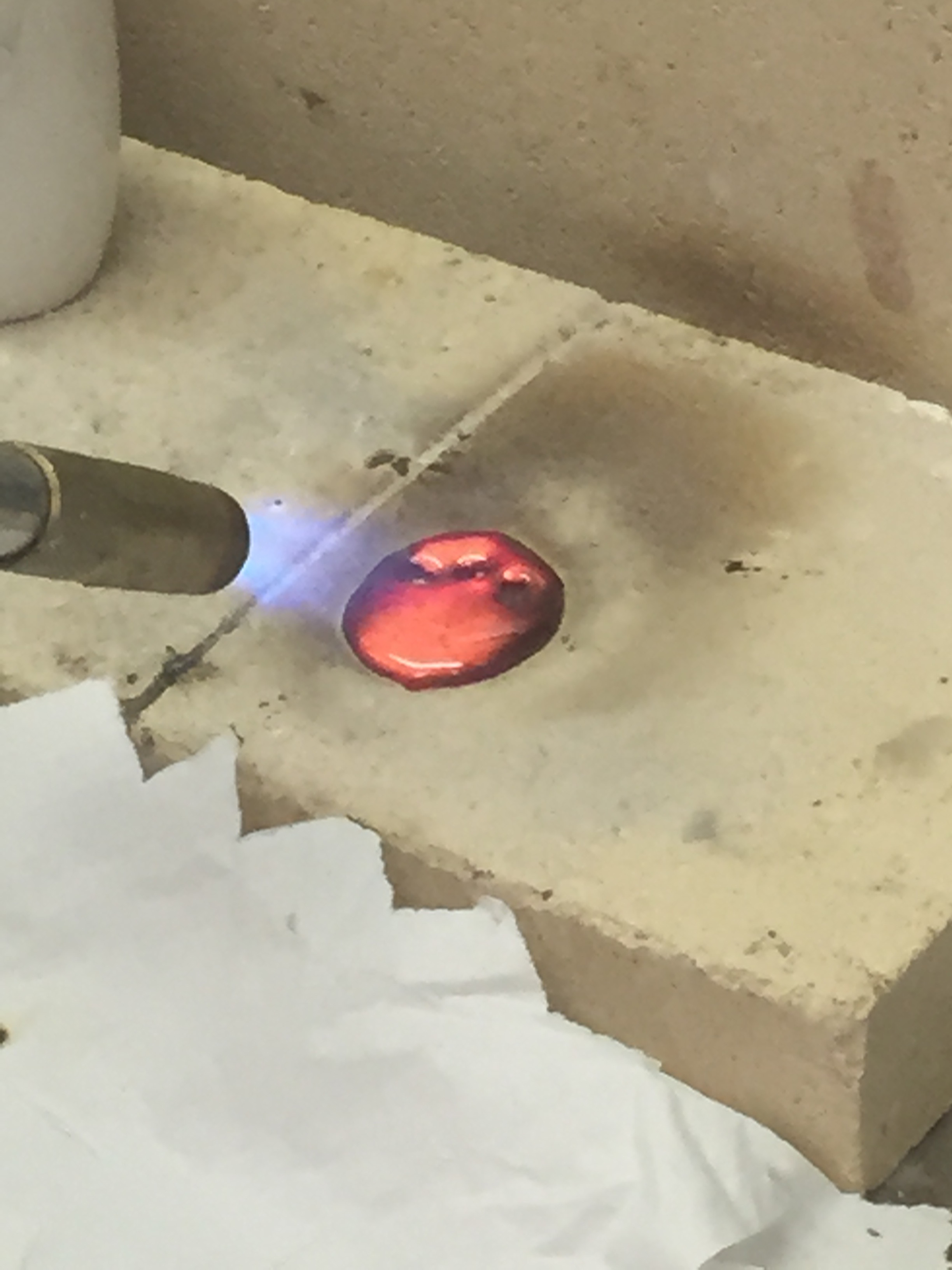

There was discussion of whether or not heat the crucible with or without the lid. We referred to the drawing of the furnace on the manuscript page. It looks a bit like underpants (at first...to someone like me who hasn't seen furnace illustrations before) but it also sort of looks like the contraption Joel has set up in the fume hood. The recipe in the manuscript says nothing about placing the lid on it or not so we look atSelf built furnace from Joel set up in fume hood, fire torchsee drawing on fol. 101vwe put the covered crucible into the furnace.we rehearsed what to do in case of emergency, explosion: try first to get torch out of fume hood. close slash of fume hood. leave labwe started as low a flame as possible with our torch in order to not break the crucible.Time12.12 we started to heat the crucible after 1 minute still at room temperature12:13 Joel turns heat up on torch12:14 temperature of the lid raises over 200 celsius12:17 over 300 celsius12:18 over 400 celsius12:23 above 500 celsius our thermometer cannot measure higher temperatures12:30 Joel thinks we now reached about 1500 celsius12:33 joel lifted the lid. its def smolten and fluid, bright red. he can pour itJoel said about 10 minutes of good heatingWe need to go up to about 1500 celsius to reach the melting point of quartz to which alkali salt is addedJ: interesting exeperience when pouring it, it's heavywe observed amazing color changes: bright red in crucible, dark red when poured out, on surface it turned darkish greyish green and it "froze" while pouring. We poured it into a silicon mold and this is where it started to start changing colors very quickly (burned the mold). It was cooling so quickly that a "string" of the liquid started solidifying while it was being poured, forming a thin, slightly undulating needle of glass. It was so hot that it started burning the mold and so we quickly removed it. When we lifted the "glass stone" (with its tail/needle) and rested it on the furnace stone it turned darker and darker and then broke open, showing that it was sort of a very fragile glass bell. it took the impression of our mould very well. Pamela noticed a bubble at the surface and this was the first piece to shatter.it turned darkish blackish green, but the thin glass fiber remained transparent with traces of greenish. when cooling the impression still seemed to change color. turning a little bit lighter green again and slightly goldish.we might have heated it too much as pamela recalls that if it is heated too much it turns black.The color seemed to change slightly for several minutes, even while the glass was cool enough to touch.12:54--inspecting the crucible and it is markedly more green inside than the black stone. As it is pulled out, within moments (less than a minute) the color starts changing. It becomes less green and more black, and then it starts cracking. This seems to be related to how quickly it is cooled. The crucible was kept in the heat chamber and allowed to cool organically, therefore this could be related to why it stayed a greener color than our black glass/stone.

-need to go up to 1100/1200 celsius (to melt copper)

questions:

was it heated to high?

will it require gold to turn red?

color of ruby to green briefly to black--was it cooled too quickly?

-remove crucible lid when stuff inside is molten

Name: Kathryn Kremnitzer, Siddhartha Shah, Joel Klein

Date and Time:

2015.10.29

Location: Making and Knowing Lab - Room Temperature is approximately 20 degrees celsiusSubject: Imitation Gems

Emerald Trial 2

tag photos with title:

2015_001fall_labsem_Kremnitzer, Shah_gemimitation_20151029_001.jpg

Emerald Trial 2: (without copper or gold)

12:50pm: Firing clay mold with impression by metal object found in lab to eventually pour glass into

12:52pm: Laying down damp paper towels in clean fume hood

12:56pm: Weighing ingredients directly into crucible using plastic spoon to measure - 3.4 grams of quartz powder, 3.4 grams of potash, and 10.6 grams of red lead

1:00pm: Placing uncovered crucible in furnace

1:03pm: Slightly heating furnace with torch

1:04pm: Put furnace top on; 60 degrees celsius

1:05pm: 110 degrees celsius - cannot see if mixture is melting; does not appear to be melting

1:06pm: 165 degrees celsius

1:07pm: 400 degrees celsius; pausing heat to fix furnace (readjusted) - no glass yet

1:09pm: Switching to a more powerful torch - immediately red hot with new torch, 650 degrees celsius; 700 degrees celsius

1:10pm: Trying to hold temperature at 700 degrees celsius; mixture is starting to melt

1:11pm: 800 degrees celsius; removed heat to check mixture - glass is relatively molten, could use a little more heat

1:14pm: 875 degrees celsius; 900 degrees celsius - molten, red hot (glowing), ready to pour - heating for a moment while it still mixes at 900 degrees celsius

1:16pm: Removed heat, removed crucible from furnace, poured molten glass into heated mold using crucible tongs

VIDEO IMG_8481.m4v

1:17pm: Using torch to keep mold hot to prevent cracking

1:19pm: Paused heat to put fire bricks around mold to help it cool more slowly

1:20pm: Got most of glass out of crucible but heating crucible in furnace again to try to get it all out

1:23pm: Pouring remnants onto heated fire brick

1:24pm: Heated remnants not flowing - think we can still use crucible; poured glass in mold is already cool enough to the touch

1:25pm: Glass immediately broke when trying to remove from mold with metal pick, not a strong glass! Dirty in color, looks like we got sand from the mold; breaks as it cools but does not shatter

Questions/ Comments from Trial 2:

1. Why is the glass green? The glass should be clear in color whereas ours is close to color of soda glass Is the green a result of impurities in the quartz? Can we was this quartz powder to rid it of impurities? Should we buy glassmakers quartz powder? Maybe the color will clear up as the glass cools to room temperature?

2. Guess that we are using too much potash - hence the green color - which relates to the unresolved issue of "un gros de sel" - we are still unclear as to what exactly "un gros de sel" means in terms of measurement. There is however a unit of measurement called a gros which is 3.842 grams

Before we incorporate copper, we will retry this procedure with less potash to see if we can get a clearer glass

1:38pm: Glass from trial 2 is at room temperature, does not break when touched

1:39pm: Cleaning up - throwing away clay - going to stick with sand mold

Emerald Trial 3: (without copper or gold)

2:12pm: Measuring 3 ingredients directly into crucible: 3.5 grams of quartz powder, 0.8 grams of potash (1/4 dram), and 10.6 grams of red lead

2:18pm: Mixing ingredients

NOTE that potash acts as a flux - we could not melt quartz in this furnace on its own because we would not be able to have a high enough heat

2:21pm: Notice that glass in trial 1 crucible is a different color than glass that was poured into mold - makes us think we should mix ingredients in trial 2 crucible more thoroughly

2:22pm: Heating uncovered crucible in furnace - letting furnace equalize a bit (with spurts of heat on and off) so we do not crack the crucible going forward

2:25pm: Begin actual heating; 775 degrees Celsius

NOTE that we think the thermo cup cover may have been a bit off in trial 1 and our temperature read therefore potentially inaccurate

2:26pm: Not molten yet - we are using less of a flux so we guess that we will have to go hotter to melt the mixture - shooting for 1000 degrees celsius

2:28pm: 1000 degrees celsius, glass is molten, read hot and ready to pour - pouring into same sand mold as in trial 1

IMG_8498 (video)

2:30pm: Glass is poured - did not pour as well as trial 1; cooled as it was pouring, poured bright red but within one minute turned to a clearer yellow

2:32pm: Trying to clean out crucible by scraping inside of it - we seem to be enabling the crucible - cannot remove melted mixture

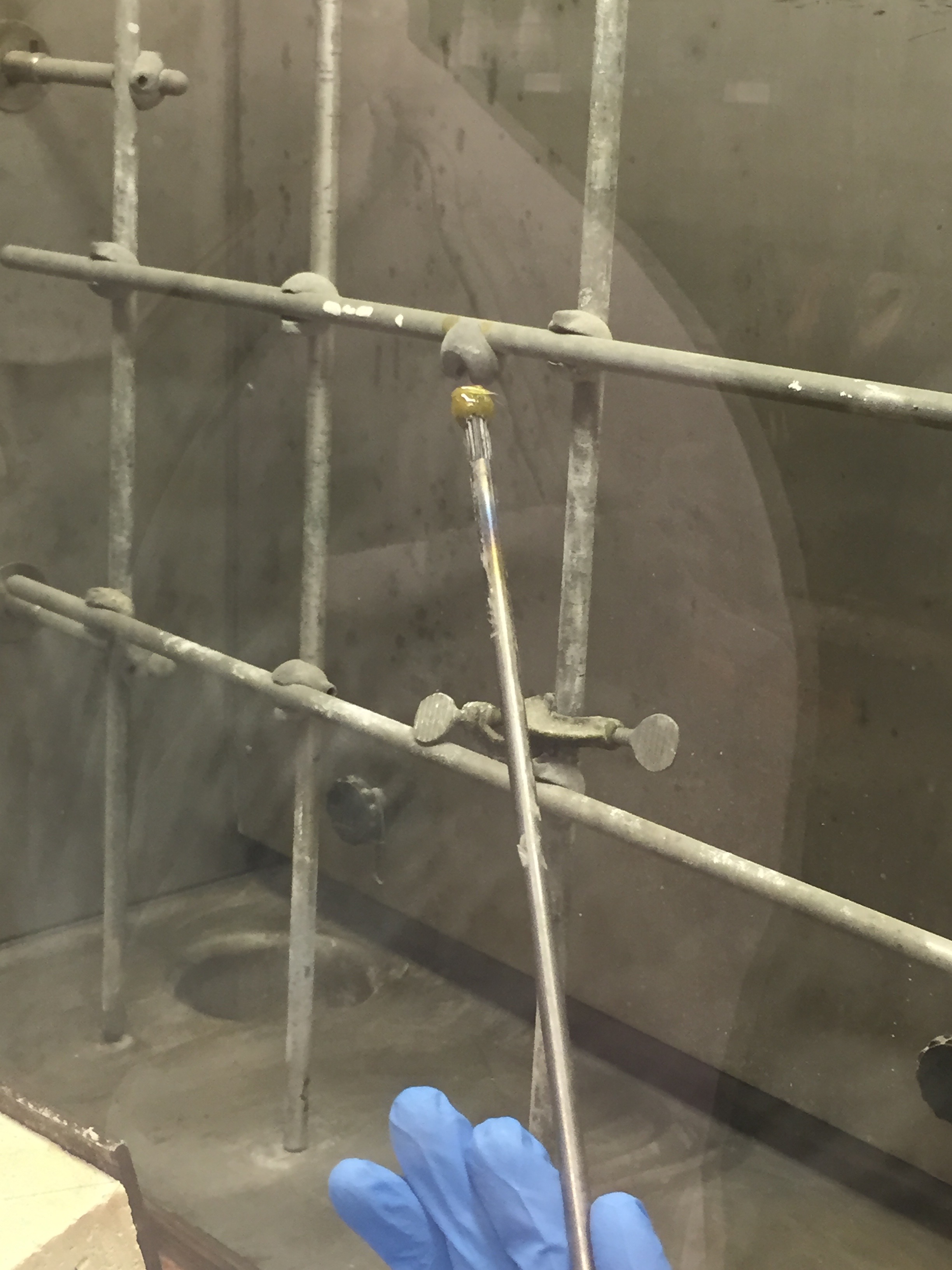

2:33pm: Heating crucible with melted mixture remnants having scraped on inside with long metal object

2:40pm: Poured glass in mold seems more stable than glass of trial 1, not breaking

Questions/ Comments from Trial 3:

Trial 3 did not pour well but the color and clarity of the glass is much improved - seems that most of the impurities are from the potash considering this glass is less green than the previous trial which used more potash

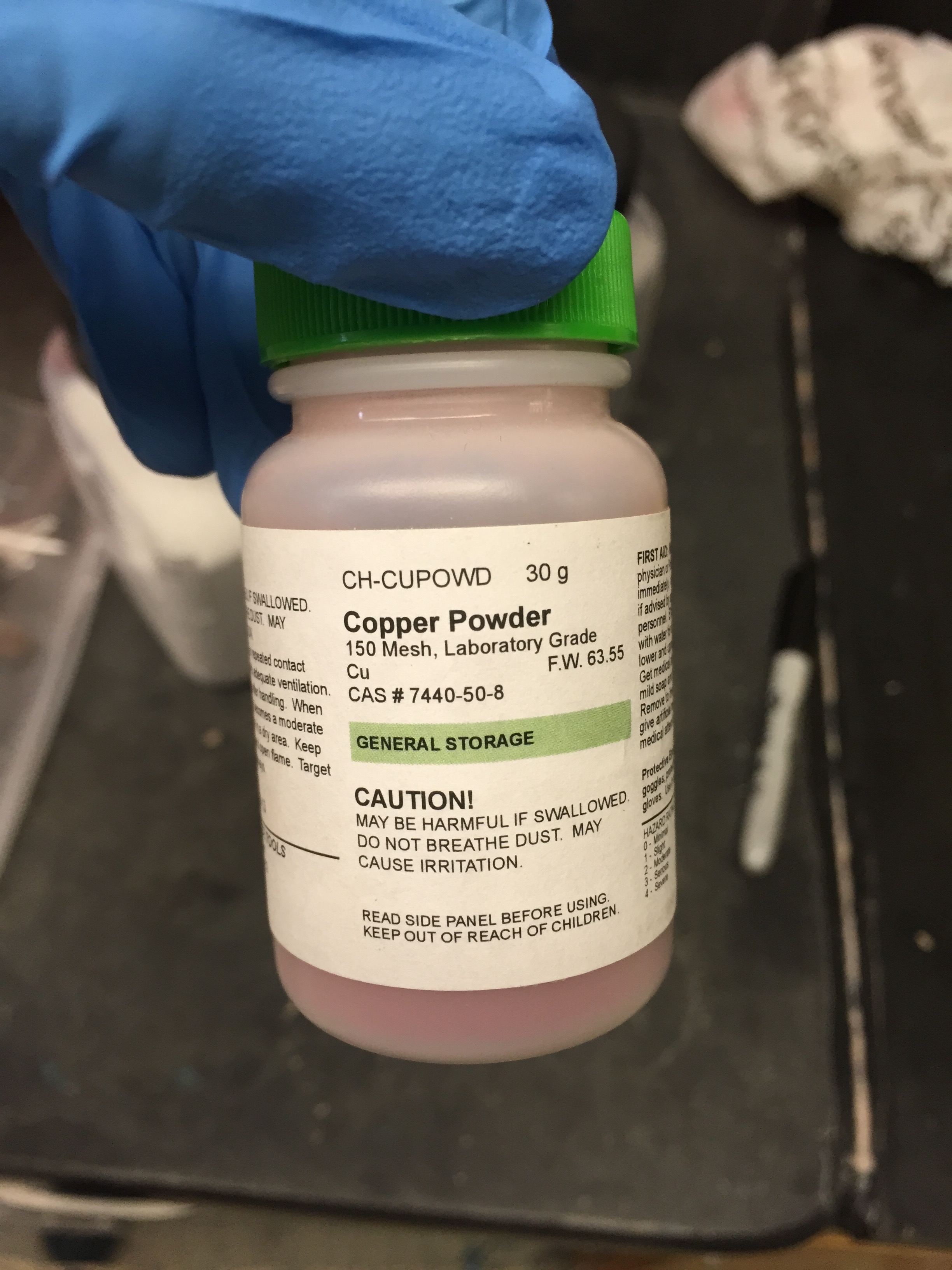

Emerald Trial 4: (with copper)

Weighing 3.54 grams of quartz powder, 1.5 grams of potash, 10.6 grams of red lead, and 0.3 grams of copper in a plastic cup (because crucible from second trial is still hot)

We are adding copper to our previous procedure and slightly increasing the amount of potash used in trial 2

The scale had a delayed reading of the copper which accounts for the 0.3 grams of copper used as opposed to the planned 0.2 grams of copper to be used

2:57pm: Grinding mixture with plastic spoon and using bottom of beaker to pound potash

2:58pm: Putting mixture into dirty crucible (from previous trial) to heat (uncovered) in furnace

3:00pm: Slowly heating furnace with torch, letting it equalize a bit off heat

3:04pm: Mixture is not quite melted yet

3:06pm: Pre-heating sand mold pre-pour

3:07pm: Mixture is molten and ready to pour - poured easily. Glass is dark green in color - letting it cool protected by fire bricks

IMG_8514.m4v

3:08pm: Reheating crucible in attempt to pour remnants

3:12pm: Successfully poured most of remnants - glass is very green

IMG_8515.m4v

Our poured mold glass is quite opaque - thinking it should be more translucent

3:17pm: Broke glass in trying to remove from mold - decide to pour directly onto fire brick next time

Questions/ Comments from Trial 4:

Those areas in which the glass is more thinly covering the inside of the crucible are most green - guess we could have poured the glass more thinly in the hopes of it being more uniformly transparent.

Washed bits of broken glass in attempt to remove sand (adhered from mold) but could not remove

Ruby Trial 1: (with gold)

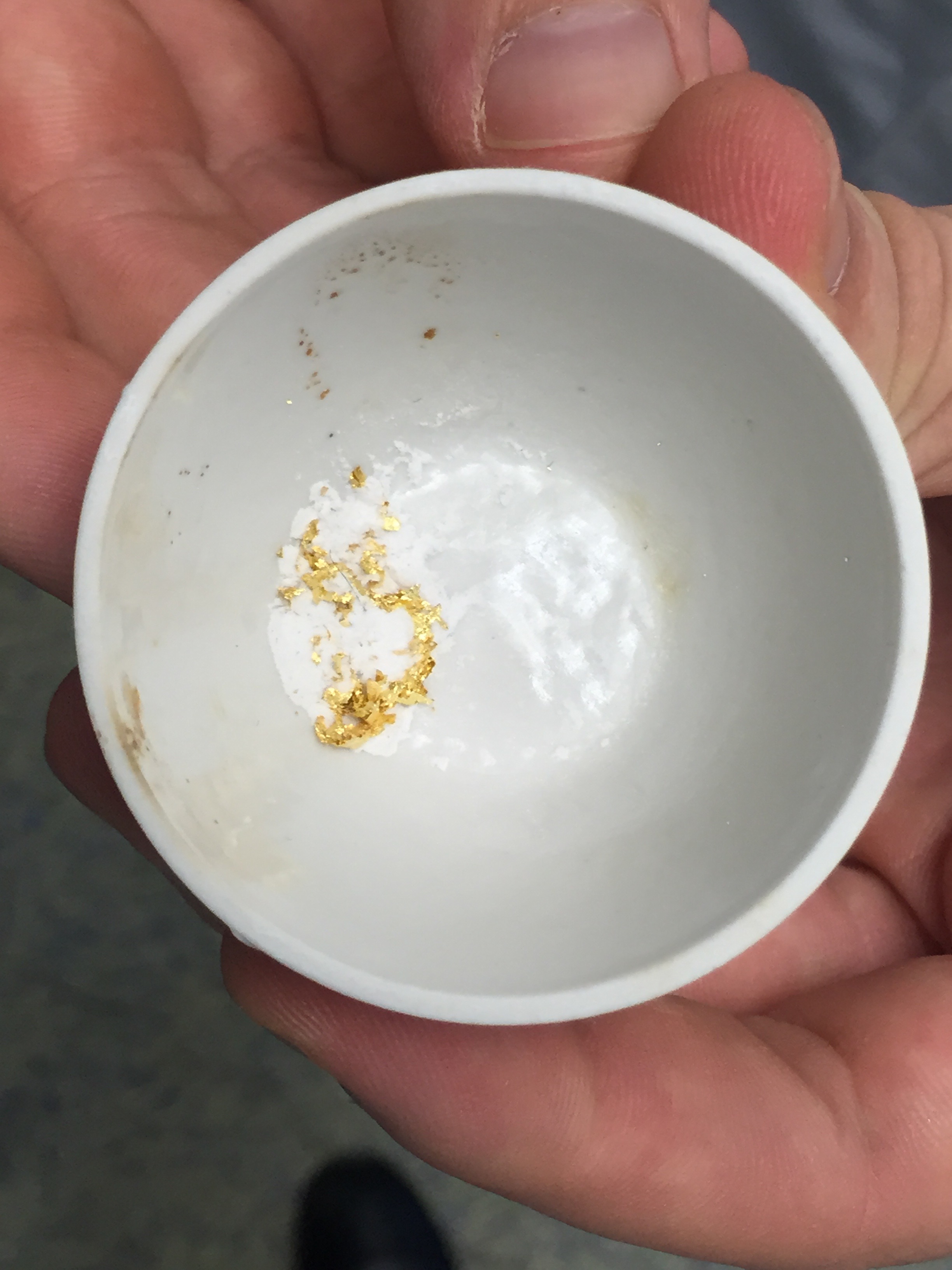

3:32pm: Suspicion that we will not have enough gold - the recipe calls for 1 grain of gold. In measuring one sheet of gold foil (85mm square), we have 0.013 grams or 0.02 grains of gold. Decide to cut recipe by 1/5 to accommodate smaller amount of gold.

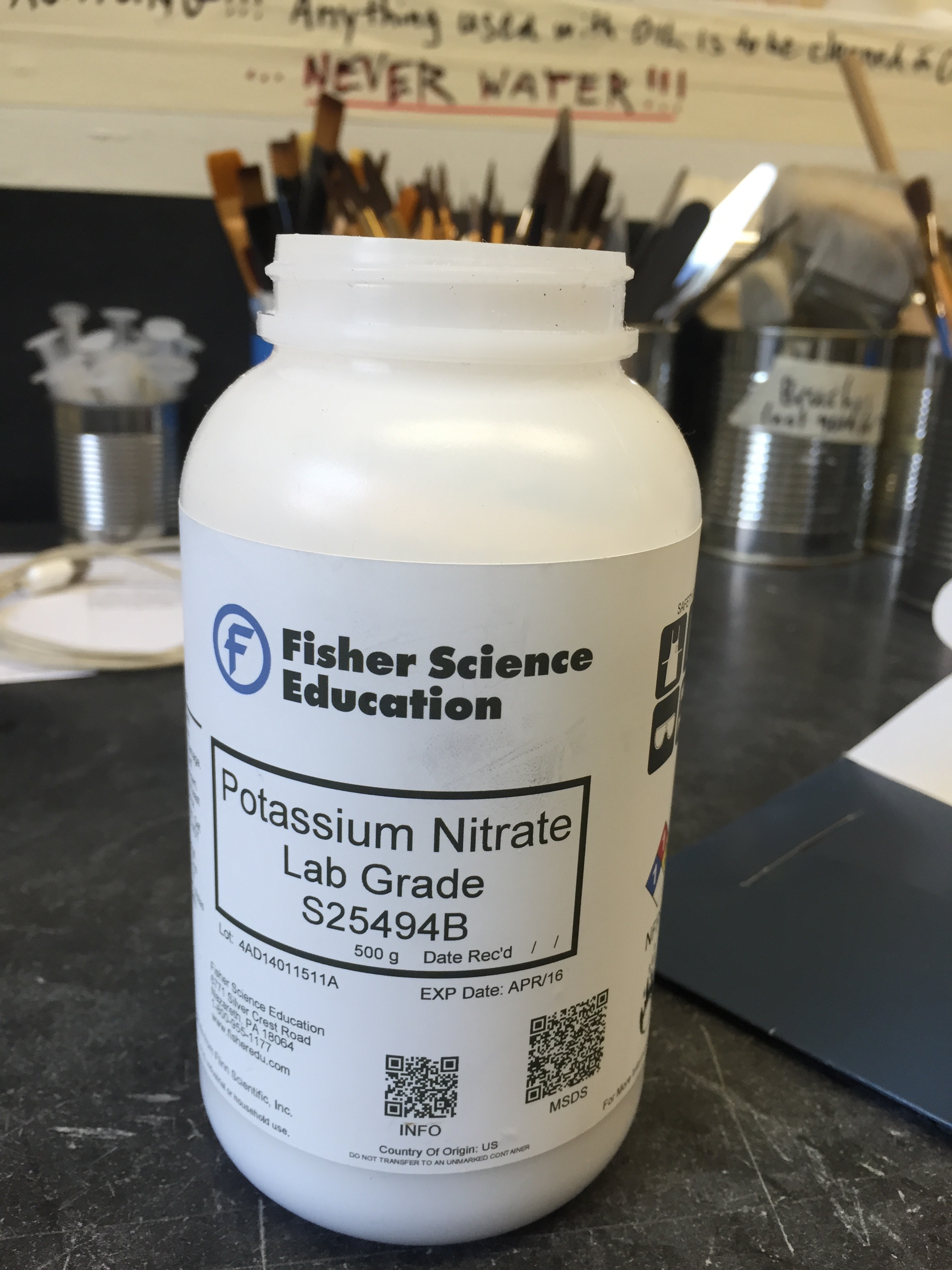

NOTE that Saltpeter (potassium nitrate) acts as flux - quarts melts at 1670 degrees celsius - we cannot get that hot with our furnace, so we want to for what the manuscript calls a "peach tree" color (in a marginal note) using saltpeter

4:00pm: Measuring 0.1 grams of quartz powder and 0.1 grams of potassium nitrate in a crucible

4:03pm: Grinding mixture in crucible (not on glass surface with glass pestle as manuscript calls for because afraid we will lose too much material)

4:08pm: Putting uncovered crucible in furnace - removed one of the two fire blocks

NOTE that potassium nitrate can be explosive

4:13pm: 1000 degrees celsius but think it may be hotter at bottom

4:13pm: Stop heating; letting glass cool off in crucible because there is such a small amount that we do not think we will be able to pour it out

4:18pm: Not all gold melted, would need more heat

Emerald Trial 5: (with copper)

0.05 grams copper

3.5 grams quartz powder

1.7 grams potash

10.6 grams red lead

4:28pm: Mixing all ingredients in dirty crucible (from a previous trial) - note that there is glass at the bottom of the crucible that had no copper in it

4:29pm: Heating uncovered crucible in furnace at full blast right away (no equalizing)

4:31pm: Stop heating but see that mixture is not melted, put heat back on

4:34pm: Checked mixture and need to keep heating

4:36pm: Poured molten mixture onto fire brick; noticed that crucible cracked - leaked into furnace. Some bubble occurred in pouring - using heat (torch_ to try to reduce presence of bubbles. The mixture is moldable when hot.

IMG_8539 (video of pour)

IMG_8541 (video of malleability)

Enameled crucible to furnace - have to break it out

4:55pm: Breaking poured glass off of fired brick

Questions/ comments from Trial 5:

Thinking we can get away with less copper; if heated longer, we would get better mixing ie. better melting.

Unable to determine what effect the breaking of the crucible may have had on the final product.

Should try grinding on a "copper mordant" in forthcoming trials

Note that all examples as of 11/9/15 crizzled, we think from the high presence of salt

Siddhartha V. Shah, Katie Kremnitzer, Joel Klein

Making and Knowing Lab

IMITATION GEMSTONE--EMERALD

2015.11.12

12-2pmEmerald Trial 6: (with copper)

SS:

12:15pm: We have begun to reheat the broken pieces from trial 5 (KK/JK) which is the trial that had the largest amount of copper (0.05g). While the experiment produced a very dark, rich green colored “gem”, the object shattered into numerous pieces and significant crizzling is visible. We are attempting to turn the pieces into a single “gemstone” by cooling it slowly by remelting it, pouring onto a granite slab and placing the hot “brick” on top.

12:21pm: Joel has begun heating all of the pieces from trial 3 on the granite slab with a blowtorch.

12:24pm: heating now on a broken piece of crucible rather than directly on granite and then going to pour onto granite slab

| IMG_0099.JPG |

| IMG_0100.JPG |

12:25: already quite melted

12:26: under the flame the emerald looks quite black with bubbling on the surface.

| IMG_0102.JPG |

12:28: we have stopped heating, entirely poured green mixture onto the granite, Joel placed the brick on top to cool it slowly.

| IMG_0103.JPG |

approx 10 minutes later: it has maintained its shape but the surface has a textured and sort of mat finish, likely due to the texture of the brick.

| IMG_0109.JPG |

Emerald Trial 7: (with copper)

we are following the proportions used in trial 5 except we have reduced the copper by half. Instead of 0.05g we are using 0.025g. We are maintaining the same amount of salt and we will heat it longer so it is easier to pour, and then we will cool it slowly in hopes that it will not crack. We will do this by covering the poured “emerald” with a crucible.

12:51 Joel is heating, and suggests that we heat for at least 5 mins to get it “really molten”. He is also heating part of the granite slab where he will pour the molten mixture because we do not want the surface of the granite to be too cool and, therefore, to increase the likelihood that the “gem” will crack/shatter

12:54 temp is 805C

12:56 stopped heating

12:57 poured and covered….waiting

| IMG_0115.JPG |

| IMG_0118.JPG |

| IMG_0119.JPG |

12:59 taking an unmeasured amt of potash and adding it to the used crucible to see if we can “clean” the remnants out

1:01--our trial is a lighter green (perhaps too light to pass as a South American emerald but passing as an Afghani emerald...I am using these descriptives based on recent readings on the colors of emeralds and regional differences as noted particularly in the 16th c) and still quite shiny.

| IMG_0157.JPG |

| IMG_0149.JPG |

It has not shattered. It has internal fissures that look more like glass than the “veins” and/or imperfections one typically finds in emeralds. The imitation we just produced has a beautiful green color and glossy luster. When held up to the light, however, it seems a bit cloudy inside. Sort of granular or speckled…

| IMG_0138.JPG |

| IMG_0127.JPG |

For the next attempt, we are going to grind the potash more finely and stir the mixture while it is molten to see if this reduces the cloudiness of the “gem”.

1:04 pouring remnants

| IMG_0161.JPG |

| IMG_0137 (1).JPG |

1:08 we are going to redo the experiment now using more copper than the trial we have just completed (trial 6--0.025) but less than trial 3 (0.05)...so we are using 0.038g of copper.

There is some discussion now that perhaps the manuscript author did not actually try this experiment--Joel is discussing how the recipe yields a dark glass, calls for “un gros de sel” which seems to be too large an amount….there is consistent crizzling which seems to be due to the amount of salt used?? This brings us back to our very initial discussion of what “un gros” actually means in the context of this recipe. Katie and I both still believe that it means something like “a pinch”. Furthermore, how do we know that these imitation stones didn’t crizzle when they were made originally? We are wondering whether oiling the “gems” might solve the crizzling issue.

Emerald Trial 8: (with copper)

1:20 all materials added and Joel is going to stir them all “very well”...one minute of stirring using the handle of a plastic spoon.

| IMG_0156.JPG |

1:22 Joel is heating and wants to heat for more than 5 minutes this time (a little bit) so that we can stir the mixture more easily and thoroughly

1:26 Joel is stirring mixture in crucible

| IMG_0136.JPG |

1:28 it’s been 6 minutes. He is going to get it up to 900 degrees (as last time) and then pour. POURED and covered.

| IMG_0159.JPG |

| IMG_0129.JPG |

| IMG_0163.JPG |

1:29 heating remnants in crucible to 1000.

1:30 done heating

1:31 a few drops of the heated remnants are the color of peridot. Joel thinks this could be because most of the copper poured out in the first pour. This could also explain why the interior of the crucible is so close to yellow

| IMG_0154.JPG |

| IMG_0160.JPG |

| IMG_0140.JPG |

1:42 The result is, in my opinion, the most successful of all our attempts. There is a bubble in it at the top which is just above a slightly stained, rough, mat portion of the bottom which made direct contact with the granite. This could be because of some kind of coating on the granite slab that came off. The color is very close to that of a genuine emerald and the luster is very fine--shiny, smooth, reflective.

| IMG_0133.JPG |

| IMG_0152.JPG |

| IMG_0198.JPG |

1:52 last trial just cracked in my hands after taking photos of it.

Considerations for next trials:

-we have been using copper powder instead of just grinding on the copper sheet to insure that we have enough copper to make the result green. Now that we have made several attempts with different amounts of copper, it might be interesting to record the amount of time it takes to collect a comparable amount of copper powder by grinding on a copper sheet and collecting the dust

-the small “peridot” beads we produced are quite beautiful and convincing. Perhaps we should try pouring the emeralds in small amounts rather than all in one “medallion”. It would be interesting to see if small drops would look even more convincing than the single medallions we have been attempting to produce

NOTES:

11.16.2015 - Conversation with Pamela Smith, Sam, Siddhartha, Katie

recipe may have been collected by a glassmaker

goldsmiths knowledge

red enamels to find processes re: imitation gems - rouge claire (much older material)

gold ruby glass (seems to have been lost by 17th century)

Joanith at Walters re: limoges enamels

Glass of the Alchemist, Corning Museum by Ditto van Krossinberg Krosik

-sought after by the Alchemists because red was associated with red and the philosophers stone was supposed to require a red powder which you could cast over your metal mass and it would turn to gold - making of vermilion (sulpher and mercury) gives you red pigment is associated with gold for various reasons - through the making of that pigment that people began to associate sulfur and mercury as two metals that when brought together form red and that red indicates that you could make gold out of it - red glass as demonstration of that, going in the opposite direction - THEORY OF MATERIALS/ MATERIALS THEORY - about connection between materials - red, blood, mercury and suffer, and gold - COMPLEX of materials which forms a theory - if you are trying to make a red color you’re going to add gold, if you’re trying to make gold, you’ll add red - why Alchemists were so interested in ruby glass as a demonstration of that principle

Green and red are also associated alchemically - copper is red as a metal but it produces green; what is the connection between gold and green - alchemical symbol as green and red

The Art of Glass, Neri [RARE BOOK BUTLER B666.1 N3562]

Rouge claire - red enamel on gold - even the bol on panel canvases, the red warms the gold it enriches it - you do not see the cracks as much - essential connections between materials is demonstrative of working within a theory

Palissey and Paracelsus - salt as basis of everything part of mercury salt sulpher triad - developed further East in Islamic alchemy and chemistry

Theory of distillation based on salts re: mixture of materials - seems to have been important for Paracelsus forming his theory, Palissey re: salt - widespread use of salt throughout manuscript - indicate importance of salt

Emeralds came from the East before South America - they had been expensive, not very nice - South American emeralds brought greater variety re: sizes

What kind of imitation gems appear in the Stockholm and Leiden papyrus

Are these imitation gems actually objects of luxury - glass itself as imitation of cristallo glass - a luxury glass - so is this luxury object by way of connection to cristallo glass - PS: yes, it is luxury, what is the purpose of imitation gem stones - interest in imitating - Frick enamels with enamel imitation gems which looked more jewellike - that’s about showing how you can imitate - levels of imitation - can imitate in the same material jewels - material mimesis, the art of art

(Joel joined conversation)

Joel explained that he has gotten better at pouring - has a sense of how much to pour when it’s ready, how long glass stays molten, at what speed it should cool

What kind of oil did they use - apparently when emeralds are mined they are immediately put in oil, the blade is then oiled after cutting

Ruby glass as one of the most famous to make, notoriously difficult to make - solved by Johann Kunkel in the late 17th century in Berlin

In looking at rouge claire recipe in BnF640 (124v) - the gold needed is an escu-pistolet - a gold coin in production between 1562 and 1586 - a Swiss cantons Geneva coin [__http://www.ngccoin.com/price-guide/world/swiss-cantons-geneva-ecu-pistolet-fr-249-1562-1586-cuid-137898-duid-341255__]

Thinking for the recipe re: color of a peach tree - we will use .002 grams of gold (a “grain”)

Question as to how much saltpeter we would need - there is no amount specified - going to try to substitute the amount of potash with saltpeter

101r calls for addition of lead - thinking that he does mean to add lead to the ruby recipe but does not specify its addition in ruby

"The first experiment I made..." only left a yellow mass - with gold grains - HE TRIED THIS AND IT DID NOT WORK - try cemented gold with antimony

Read section on Topaz

Check Agricola, De Re Metalica re: furnace tiles (Book VII)

https://books.google.com/books?id=MfFYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA225&lpg=PA225&dq=agricola+de+metalica+furnace+tiles&source=bl&ots=menOZHk_vz&sig=AO6gPNHCas8xJCjxK_kPhHNV9S4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAGoVChMIwavR4LSVyQIVQhw-Ch3xowgr#v=onepage&q=tiles&f=false

Possibly an image of a tile furnace in illustrated copy?

Re: "raising by two tiles" ("Haulsse ton four de deulx tuiles")

Seems that author-practitioner tried to make ruby glass several times and never succeeded - look for clues in the topaz recipe. Seems that our author-practitioner did not know the secret of red ruby glass - either source from which he took recipe did not know or withheld necessary information

Look for medieval sources on leaded gemstones

Furnace conditions not discussed in Renaissance manuscripts but that in the Middle Ages there was a way of doing it.

GOING FORWARD:

POUR SMALLER BEADS

PUT THEM IN STAND OIL, LINSEED OIL, AND NO OIL

PUT THEM ON GOLD FOIL TO SEE HOW THEY WOULD LOOK AS SET

2015.11.16

LabKathryn Kremnitzer, Siddhartha Shah

Ground verdigris around 1PM to paint onto two stones (one generic river stone and one we think was crystal - was very shiny and totally transparent)

Coated both stones with verdigris ground with linseed stand oil in keeping with Marolijn's trial we found online (http://recipes.hypotheses.org/4659)

Then painted out the verdigris onto square 1C of Katie's board, painted out verdigris with mixture of linseed stand and regular linseed oil on 1B, and painted out brush to clean on square 2C after quite a bit of cleaning in linseed oil.

Plan for Monday, November 23

Do another emerald trial with enough yield to make three batches of small glass beads - one to be put in stand oil, another to be put in linseed oil, and another to be left alone (without oil) with enough in this group to share with Anna and Wenrui to try grinding into a pigment and painting out

Maybe we can also turn our attention in part to the below recipes for Topaz and Hyacinth (yellow stone) on pp. 101r, 101v of BnF 640

<id>p101r_1</id>

<head><m>Topaz</m></head>

<ab>The same dose is used for all jewels, which is one weight of calcined <m>pebbles</m> with three weights of <m>minium</m>, all pounded separately in a <m>copper</m> mortar for <m>emeralds</m>, and in an <m>iron</m> mortar for <m>topazes</m> or <m>amber</m> color, with pestles of the same <sup>matter</sup> as the mortars. <m>Emeralds</m> and <m>topazes</m> need to be heated at the same temperature, and for an hour and a half, otherwise they could be burnt. <m>Rubies</m> need more time and stronger heat, and <sup>to be</sup> colored with <m>gold</m> leaf. I believe that for <m>rubies</m> <m>pumice stone</m> or <m>fire-stone</m> would be better. See <m>enamels</m>. Instead of pebbles, try also to mix pieces of <m>colored glass</m> or <m>enamels</m>. If the mass is not colored enough, pound it further in the <m>iron</m> mortar.</ab>

<note>

<margin>left-middle</margin>

Slightly burnt <m>tartar</m> mixed in makes beautiful yellow, but not much is needed. <m>Sand</m> also makes it more yellow.</note>

</div>

[FRENCH]

<div>

<id>p101r_1</id>

<head><m>Topasse</m></head>

<ab>La mesme doze s’observe en toutes pierreries, sçavoir un<lb/>

poix de <m>caillous</m> calcinés sur trois de <m>minium</m>, pilant le<lb/>

tout separem{ent} dans un mortier de <m>cuivre</m> pour <m>esmeraulde</m><lb/>

& dans un mortier de <m>fer</m> pour faire <m>topasse</m> ou couleur<lb/>

d’<m>ambre</m>, avecq les pilons semblables aulx mortiers.<lb/>

L’<m>esmeraulde</m> & la <m>topasse</m> sont de meme chaleur, & pour<lb/>

une heure & demye de foeu, car elles se pourroient<lb/>

brusler. Le <m>ruby</m> veult dadvantage de temps<lb/>

& plus de foeu & colore d’<m>or</m> en foeille. Je croy que<lb/>

la <m>pierre ponce</m> ou <m>pierre à foeu</m> pour le <m>ruby</m> seroit<lb/>

meilleur. Voy les <m>emaulx</m>. Essaye aussy de mesler,<lb/>

au lieu de <m>caillous</m>, des pieces de <m>vitre</m> de couleur ou<lb/>

des <m>esmaulx</m>. Si la masse n’est assés colorée, pile la davantage<lb/>

dans le mortier de <m>fer</m>.</ab>

<note>

<margin>left-middle</margin>

Le <m>tartre</m><lb/>

un peu bruslé<lb/>

meslé parmy<lb/>

faict beau<lb/>

jaulne mays<lb/>

il n’en fault<lb/>

guere. L’<m>arene</m><lb/>

aussy faict<lb/>

plus jaulne.</note>

</div>

<div>

<id>p101v_1</id>

<head><m>Hyacinth</m></head>

<ab>It is made, like <m>rubies</m>, with <m>gold</m>; but without such intense heat. <m>Rubies</m> need to be heated for a whole day, and if it does not have heat for long enough, you will obtain only reddened varnish.</ab>

<note>

<margin>left-top</margin>

Always heat up your crucibles.

</note>

<note>

<margin>left-top</margin>

It is believed that rubified <m>antimony</m> makes <m>hyacinth</m>.

</note>

</div>

<div>

<id>p101v_2</id>

<head><m>Topaz</m></head>

<ab>I melted one part of calcinated and pulverized <m>pumice stone</m> with three parts of <m>minium</m>, the stone pulverized in a steel mortar. I obtained a very nice yellow, without any one grain more yellow than the other. It is true that it was quite colorful. I think it would be better to pulverize the <m>pumice</m> in a glass mortar, since it and <m>minium</m> are yellow enough by themselves. I obtained a matter with a nice yellow on top, as I said, and the bottom as a <m>fire-stone</m> without transparency, with which, in mixing in other</ab>

</div>

[FRENCH]

<div>

<id>p101v_1</id>

<head><m>Jacinthe</m></head>

<ab>Se faict comme le <m>ruby</m> avec de l’<m>or</m>, mays il n’y<lb/>

fault pas si grand foeu. Le <m>ruby</m> veult foeu tout<lb/>

un jour, et s’il n’ha pas assés de foeu, il n’aura<lb/>

que des vernis rougis.</ab>

<note>

<margin>left-top</margin>

Recuits toujours<lb/>

tes creusets.

</note>

<note>

<margin>left-top</margin>

On tient que<lb/>

<m>antimoine</m> rubifié<lb/>

soict <m>jacinthe</m>.

</note>

</div>

<div>

<id>p101v_2</id>

<head><m>Topasse</m></head>

<ab>J’ay fondu une part de pierre <m>ponce</m> calcinée &<lb/>

pulverisée avecq trois pars de <m>minium</m><lb/>

et la pierre pulverisée dans un mortier de<lb/>

acier, il m’est <add>venu</add> un fort beau jaulne, sans aulcuns<lb/>

grains plus jaulne que nul aultre. Il est vray<lb/>

qu’il estoict chargé fort de couleur. Je croy qu’il<lb/>

seroit mieulx de pulveriser la <m>ponce</m> dans un<lb/>

mortier de verre, pource qu’elle & le <m>minium</m> font assés<lb/>

jaulne d’eulx mesme. Il m’est venu une masse, le dessus<lb/>

beau jaulne co{mm}e dict est, le dessoubs co{mm}e <m>caillou à<lb/>

feu</m>, sans transparence. Avecq quoy, en meslant d’aultr</ab>

</div>

*indication here that author practitioner perhaps first pulverized the pumice stone in a steel mortar as suggested but then retried the experiment with a glass mortar and determined it was better

*Note that the text is unfinished...

TRIAL 9

2015.11.23

LabKathryn Kremnitzer, Siddhartha Shah, Joel Klein

FINAL EMERALD TRIAL

We are doubling the measurements of our last furnace trial to yield enough material to oil samples (in walnut and linseed oil) and to give some to Anna and Wenrui to grind into pigment. Hoping to pour small beads as opposed to a singular medallion

6.82g quartz powder

3.4g potash (ground with pestle in plastic bag)

0.05g copper (measured 0.07g with assumption that not all poured into crucible)

21.2g red lead

We are using a different crucible than our previous trials - this crucible is more bowl like (wider and shorter)

12:13 PM all ingredients measured and mixed

12:19 PM began heating, going to start heating covered crucible slowly and periodically heat granite surface onto which we will pour

12:21 PM forgot thermocouple to measure temperature in furnace - removed crucible to fix

12:22 PM 74 degrees C outside, putting crucible back in furnace - immediately have 500 degrees C ambient temperature inside furnace

12:25 PM mixture is turning darker red inside crucible

12:29 PM crucible is not getting hot enough (it is further away from heat than previous trials given difference in size) - need to remove the top brick to get more direct heat

12:31 PM successfully removed top brick, resuming heat - immediately hotter, bubbling inside, mixture is dark brown, no longer red

12:33 PM stirring mixture with metal rod; trying to get mixture as molten as possible

12:35 PM crucible lid cracked

12:36 PM poured mixture rapidly over granite surface to make small beads - covered some with crucible lids ad left some uncovered - letting poured glass cool, preparing two beakers of oil (one walnut, the other linseed)

*metal rod used for stirring has potash and melted remnants

12:46 PM glass is at room temperature - taking small samples to oil

12:48 PM divided glass samples into three groups, two to be oiled, the third to be ground for pigment

Walnut oil:

Linseed oil:

ALL TRIALS INCLUDING VARIOUS OILINGS:

Trials 1-8 (left to right); oiled in walnut, linseed, and unoiled (top to bottom at right)